Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument in south-east Montana is a solemn place. Foolhardy bravado, a clash of cultures and deadly bloodshed have forever marked its place in the pages of history.

White man came across the sea

He brought us pain and misery

He killed our tribes killed our creed

He took our game for his own need

We fought him hard we fought him well

Out on the plains we gave him hell

But many came too much for Cree

Oh will we ever be set free?

Run to the Hills – Steve Harris, Iron Maiden (1982)

Indian Reservations

Since the first European colonization of North America, a seed was planted that would slowly but surely destroy the way of life of Indian tribes and lead to a long and bloody conflict. Western expansion by settlers had shown little regard to the Indian way of life, hunting grounds and so on. They were pushed out of their traditional lands and would strike back accordingly.

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 was a law passed to move them away from European populated areas and supposedly stop further conflict. The Indian Appropriations Act of 1851 paved the way for the establishment of Indian reservations in what is today Oklahoma. The forced relocations obviously didn’t bode well with Indian tribes, especially those who traditionally lived a nomadic way of life. In 1868 President Ulysses S. Grant wanted to stop the violence that had risen over the years from the clash of cultures and pursued the further relocation from ancestral lands to specific designated Indian Agency areas that were overseen by white religious groups. Protests by white settlers against the size of the land allocated often saw the areas reduced.

Life for members of the Northern Plains Indians tribes such as the Lakota (part of the Sioux) and Cheyenne was supposedly set in place in 1868 with a US government Fort Laramie Treaty that promised a large area of territory as a permanent Indian reservation known as the Great Sioux Reservation that covered the western half of South Dakota, extended into parts of Nebraska and allowed for hunting in Wyoming. They could go about their way of life more or less unhindered and under the protection of the government (apart from the push to Christianity!). Life wasn’t necessarily so good with poor conditions and corrupt administration often apparently experienced across the Indian Agencies.

Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540

This remained so for a few years until 1874 when gold was discovered in the Black Hills, right in the heart of the allocated Indian territory (ironically George Armstrong Custer lead the Black Hills Expedition in 1874 that resulted in the discovery of gold, as at his behest two professional miners were part of the expedition) . Gold seekers soon came and ignored any treaties that may have been in place and tensions grew.

The Sioux War

The Northern Plains Indians had been pushed to the brink by the western expansion of white settlers. They started to leave their reservation and recommenced raiding European settlements. They were told to return to the allocated lands by January 31st, 1876 or be treated as hostile. Tribe members that did not remain on or return to the reservations were pursued by the US Army in their attempts to control the area. These types of actions lead to massacres and war. The most famous being the Sioux War that went on from 1876 to 1881 across the northern great plains.

By the summer of 1876 the US Army had commenced a campaign against the Lakota and their allies the Cheyenne and Arapaho who were now concentrated in south-eastern Montana under the leadership of Chief Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse (both were Lakota Sioux) and other chiefs. The Indian tribes were there because hunting was good in that region and they had just celebrated their annual sun dance ceremony where Sitting Bull had a vision in which he saw soldiers falling upside down into his village and prophesied a great victory for his people.

Three US Army forces set out from the Wyoming, Montana and Dakota territories under the leadership of General George Crook, Colonel John Gibbon and General Alfred H. Terry respectively to more or less surround the Indians. Here once again enters a famous name in American history, Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer was under the command of General Terry.

On June 17th, 1876 General Crook’s column was knocked out of the fight during the Battle of the Rosebud by a large Lakota-Cheyenne force at Rosebud River south of the Little Bighorn Valley that forced him to withdraw. The rest of the army forces decided to venture into the valley and confront the Indians.

Battle of the Little Bighorn

General Terry ordered Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer and the US 7th Cavalry to approach Little Bighorn from the south while he and Colonel Gibbon’s force would approach from the north. They intended to force the Lakota and Cheyenne back to the Great Sioux Reservation. That decision was one that forever made its mark in history.

Custer had found fame during the US Civil War between 1861 and 1865 as an effective, gallant yet aggressive officer, being promoted several times to achieve the rank of Major General in command of a cavalry division. He led from the front and was willing to take risks to win a battle and apparently had 11 horses shot from under him but only suffered one wound from a Confederate artillery shell during the Civil War (known as “Custer Luck”)! After the war he returned to the rank of Captain but was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and commander of the US 7th Cavalry in 1866 and continued this derring-do into the Indian Wars.

Custer had around 600 men at his disposal at Little Bighorn (including officers, soldiers, civilians and Indian scouts). On the morning of June 25th, 1876 the US 7th Cavalry detachment had located a large Lakota, Cheyenne and Arapaho camp with around 8,000 inhabitants in the camp (men, women and children). Custer had planned to conduct a surprise attack on the village at dawn on June 26th but his Crow and Arikara Indian scouts reported that the Lakota and Cheyenne knew they were there.

Knowing the element of surprise was gone, Custer did not want the camp inhabitants to disperse and escape into the rugged countryside, so he ordered the attack on the encampment to go ahead immediately. It was here Custer must have totally underestimated the fighting strength of the Indians and made the major mistake of dividing his regiment into three fighting battalions made up of eleven companies – one under his own command with five companies (210 men), Major Reno with three companies (140 men) and Captain Benteen with three companies (125 men). In addition there was a mule pack train to carry supplies and ammunition who were protected by a twelfth company of fighting men. The 7th Cavalry were to soon discover they were facing anywhere up to 1,500 to 1,800 warriors during the battle (from what I have read the US Army were only expecting a maximum of 800 warriors when they set out on the campaign)!

Custer and Reno were to attack the camp and Benteen was to scout the bluffs to the south. Custer turned north to attack one end of the encampment and ordered Reno to cross the Little Bighorn River and attack the upper end. By mid afternoon on June 25th, Reno had formed a skirmish line to fire into the encampment but was met by a vastly superior force of Lakota warriors and was soon outflanked and in a defensive retreat first into the nearby trees, then back up to the top of the bluffs where he took a defensive position and was soon reinforced by Benteen. Reno lost more than 30 men in that retreat.

Whilst this was going on Reno and Benteen could hear gunfire in the direction Custer had set off to in the north. They attempted to send a force in that direction but were pushed back and stayed in their defensive positions atop the bluff holding off the Indians for the rest of the day and into the next, until General Terry and Colonel Gibbon arrived with their soldiers forcing the Indians to withdraw (this area is today known as the Reno-Benteen Battlefield and remains of some of the entrenchments and rifle pits can still be seen). They were to never see Custer alive again.

Here is where the reality of events really strikes home. As you enter the battlefield you see Custer’s Last Stand Hill. This was the place where he and around 41 of his remaining men were surrounded by a vastly superior number of Indian warriors and fought to the end amidst fierce fighting. Horses were shot to be used as cover (a desperate last act for a cavalryman) and with the rapid-firing of guns amidst smoke and dust mayhem ensued! It was said to have all been over in a matter of minutes.

Just below Last Stand Hill are clustered a large number of tombstone like markers and you will see many more scattered across the battlefield. These mark the spots where Custer (aged 36), his brother Captain Thomas (Tom) Ward Custer (aged 31, a recipient of two Medals of Honour during the US Civil War, he was Captain of C Company but served as Custer’s aide-de-camp at the Battle of Little Bighorn) and their 210 men died during that battle (plus 53 dead and 52 wounded from Reno and Benteen’s command). “Custer Luck” had run out.

The two Custer’s died near each other on Last Stand Hill along with their younger brother Boston Custer (aged 27), who was a civilian forage master for the US Army and their nephew Harry (Autie) Armstrong Reed (just 18) who was a civilian cattle herder (he probably thought it would be a grand adventure with his uncles and was actually meant to be with the pack train, where he probably would have survived but instead he galloped off to be with his uncles during the battle and met his demise – his marker on Last Stand Hill says Arthur Reed for some reason). In addition brother-in-law to the Custers, Lieutenant James Calhoun (30) who commanded L Company died on what is known as Calhoun Hill, which saw fierce fighting with warriors such as Lame White Man (he died further into the battle in the Deep Ravine area), Crow King and Two Moons. The Custer family was decimated at Little Bighorn and the loss of five 7th Cavalry companies (C,E,F, I and L) and two US Civil War heroes shocked the nation!

Many of the cavalrymen’s bodies were found stripped of their clothes, mutilated and scalped. In addition to the mutilation George Armstrong Custer was found with two bullet holes, one in the left temple and the other just below his heart. It was a brutal fight and the aftermath was equally so (not that the results would have likely been much better if the battle had gone the other way).

On June 28th, 1876 the bodies were buried in shallow graves where they fell. In 1877 the 11 officers and 2 civilians (Boston Custer and Harry Reed) were exhumed and reburied out east (including Custer whose body now lays at rest at the West Point Military Academy). In 1879 the battlefield was designated a national cemetery. The soldiers were reburied in a mass grave that is under the 7th Cavalry Memorial built atop Last Stand Hill in 1881 and the tombstones were erected by the US Army in 1890. Nearby is a small monument to mark the place of the US 7th Cavalry Horse Cemetery.

As you wander the hill, bluffs and ravines of the battlefield, walking past and sometimes amongst these tombstone like markers you cannot help but start to imagine the sheer terror these US 7th Cavalry men experienced in their last moments with over 1,000 warriors charging them down! This is especially so in the ravine at the location of the Keogh-Crazy Horse Fight which seems to be less frequented by tourists. I wandered down there alone and took in a quiet moment to think about the soldiers of Company I under the command of Captain Myles Keogh. They were mowed down by a devastating charge led by Crazy Horse and White Bull as they attempted to retreat towards Custer on Last Stand Hill.

On the other side of the bluff is an area known as the Deep Ravine. Towards the end of the battle it is believed some of the soldiers attempted to get to the ravine but were all cut down. The tombstone like markers dot the trail all the way to the Deep Ravine. That’s a sombre walk I can tell you!

Around 80 to 100 Lakota and Cheyenne died in the battle and a few red markers indicate some of the spots where they died (put in place by the National Parks Service in 1999). Most of their bodies were removed from the battlefield to be buried in a more traditional sense by their people when the large encampment dispersed and the tribes scattered north to Canada or to the south.

Following the fierce fighting the Northern Plains Tribes had won the battle but ultimately they did not win the war and against overwhelming odds failed to fully preserve their traditional way of life. In the coming year they faced the inevitable, surrendered and returned to the reservations where their people continue to live to this day (following the defeat the US Army were authorised to send in a much larger force to confine the tribes to the reservations). The battlefield itself is now on the Crow Indian Reservation.

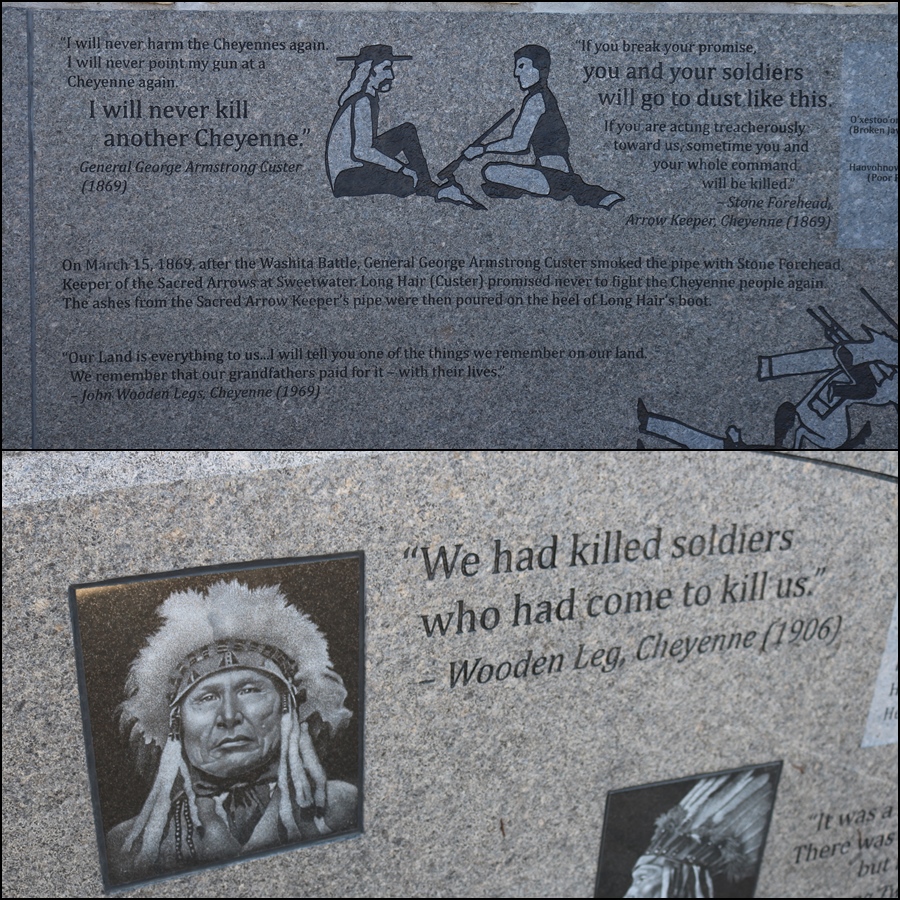

The Indian Memorial at Little Bighorn was dedicated in 2003. It expresses “Peace Through Unity” and is a tribute to their people’s fight.

Looking back at all this it is kind of hard to imagine it only happened just 140 years ago. It seems so much longer in the past.

Good Afternoon Deano, I enjoyed reading your account of the Custer last stand, having read about it often as a child. (I am 70yeras old now!) I never really understood these events until reading accounts such as yours. I have a lot of family in USA, mainly in California and Oregon. I served as a soldier in the British Army, so can see it from the soldiers point of view, and, reading your inclusions from the Indians involved, now see it from theirs as well. This is as good a tribute as anyone can expect, and I think it brings me a bit closer to my Uncle Ollie, who emigrated to USA with two of his brothers in about 1920. (All travelled steerage!) He was a cavalryman n the British Army in WW One, (Royal 5th Lancers) but survived and went on to get to USA and have kids. Kind of brings the circle around, or do you have to get to 70 to think like this? Very Best Regards from UK, Gary

Thanks Gary! Migrating back in those days was a huge undertaking and one you couldn’t reverse easily if you didn’t like it!!

Thank you for this account. I toured 2 battlefields many years ago, solo and mostly on foot, so I had plenty of time to reflect on what happened: Gettysburg and Antietam. The experiences were quite moving.

I recently read an account of this battle from the perspective of a modern Lakota, The Day the World Ended, by Joseph Marshall III, which is more about the Lakota themselved than the battle, but is valuable. It is rare in USA for people to get a Native American perspective; books written by African Americans have made it onto mainstream must read lists, but those by Native Americans.

I enjoyed some of your aircraft posts, which ended up leading me here.

Thank you. I did something similar on those battlefields. The bloody row and so forth was something that really struck home how brutal the battles were. Totally agree on untold stories of Native Americans